Chappell Roan has landed. An indisputably indomitable force, she crusades into the 2025 Grammy Awards with 6 nominations and an ever-growing legion of fans in tow. Though the release of her album The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess in September 2023 was met with little fanfare, her role as the opening act for Olivia Rodrigo’s GUTS tour in early 2024, followed by her whistle-stop run of North American festivals, rendered her and her post-album single Good Luck Babe an instant sensation. For some, it was the track’s emotive nature: for others, it was her seemingly endless on-stage energy, coupled with gaudy, clever costuming. She was a character. And she was camp.

To me and many other lesbians, she was no stranger. I first encountered her in early 2022, making her way onto my TikTok ‘for you’ page with pleas for hype around her upcoming single, Naked in Manhattan. Having been dropped by her label during COVID, she had decided to fight one more time for her art: this time not as a Missourian teenager, but as a queer adult woman. Queerness, and the queer experience, is the beating heart of her music. Chappell, as her persona, is more of a drag queen than a pop princess: she cites drag as her main visual inspiration, and queens open her shows on tour. Her songs, though produced with the inner child in mind, tell the tale of a woman exploring and making peace with her sexuality. Naked in Manhattan toys with the experimental1: “boys suck, and girls I’ve never tried” sung over an 80s synth-pop beat evokes a teen sleepover, where real attraction masquerades as ‘let’s just practice!’. Red Wine Supernova, by contrast, shows us a Chappell unabashed in her sexuality, playfully lustful.

To have pop with such overtly queer themes establish not only a place in the charts, but a place in the academy, left many queer women rejoicing. In a cultural landscape dominated by heteronormativity, Chappell, with her outspoken lesbianism, was a long-awaited relief for those of us hiding in private subreddits attempting to eke droplets of sapphicity from cryptic Taylor Swift lyrics. As such, many heralded Chappell as finally spearheading the ‘lesbian renaissance’ into the mainstream zeitgeist. I admit, a part of me celebrates with them. For the first time in my memory, ‘lesbian music’ - as my mother so lovingly calls it2 - is no longer crooning women cradling a guitar3. Good Luck Babe plays on the radio as I sit in the car with my parents. My girlfriend, who feels that prior associations of this genre just aren’t songs that she’d listen to, finally feels represented. But somehow, it still all rings hollow.

To clarify before I continue, this piece won’t be me demanding more from the industry. One, because any forced attempts at lesbian representation in the media will inevitably read as just that, and two, because I do love Chappell - very deeply. But I struggle with this concept of a ‘lesbian renaissance’ for a multitude of reasons, and more importantly, I struggle with what it means that Chappell has found herself at its helm.

To begin, I find conceptual difficulty with ‘lesbian renaissance’ as a term. To name it a ‘renaissance’ implies a prior death - of which there was no such thing. Lesbian art, and lesbian music, have persisted and will persist with or without the attention of the public. Instead, this nomenclature places emphasis on the place of said art within popular culture. The prior ‘death’ it refers to, by my estimates, is the end of the ‘lesbian chic’ movement, a trend which ebbed and flowed throughout the 90s and early 00s. To understand what it would mean to have a lesbian renaissance today, we must first delve into its history.

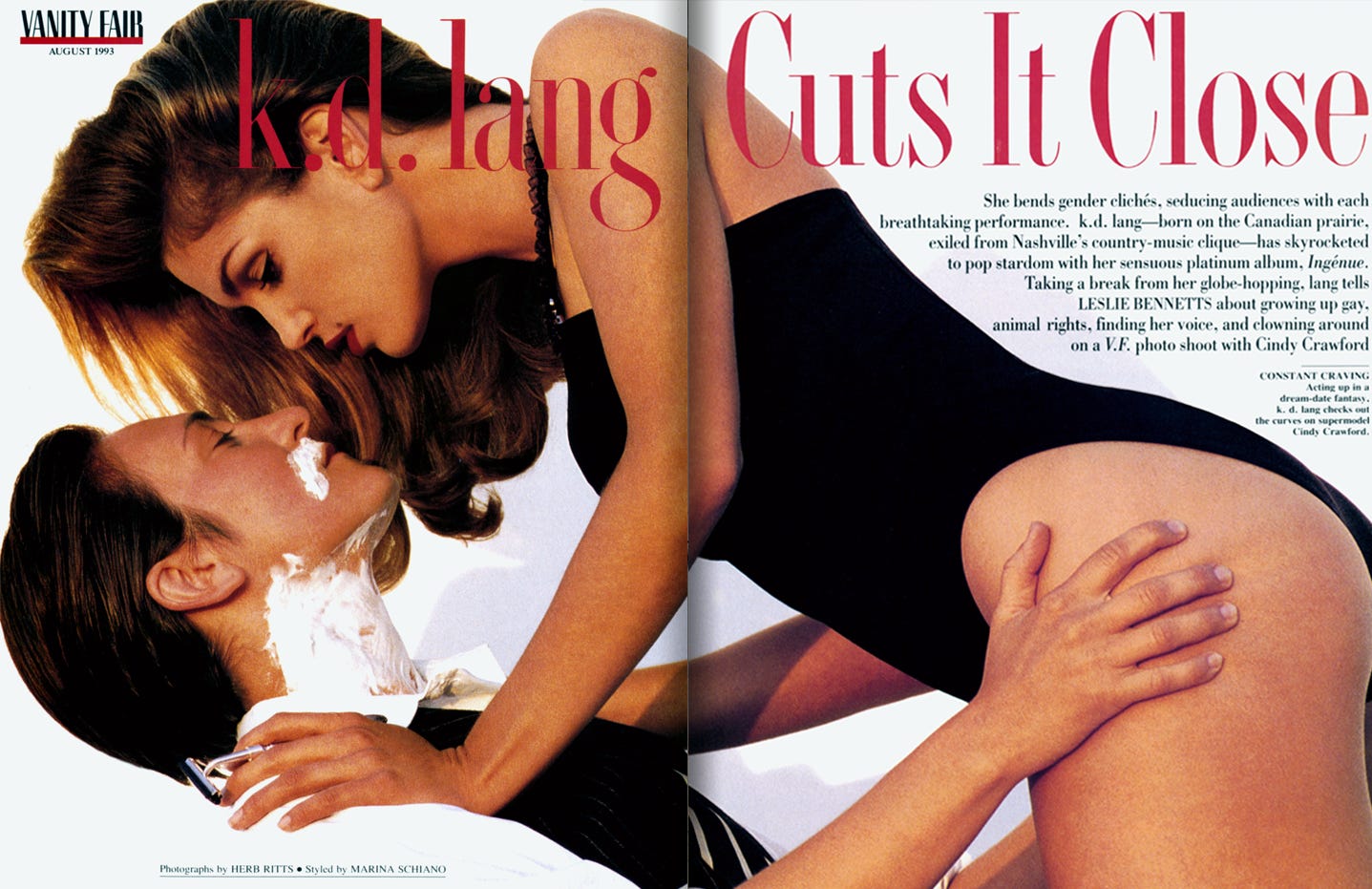

It began with a slew of magazine and newspaper headlines in 1993. New York Magazine’s May issue saw a sharply-dressed k.d. lang gazing sultrily at the reader, the title “Lesbian Chic” sprawling beneath her. lang was on front covers again in August, this time in a now-infamous Vanity Fair shoot where, lang once again in a dapper suit, a scantily-clad Cindy Crawford holds a razor to her lathered face. The message was clear: lesbians were in, and they were sexy. In an almost overnight departure from the man-hating, anti-fashion lesbians of decades past, this new generation was slick, beautiful, and above all: marketable. In the piece that accompanied lang’s May cover, writer Jeanie Kasindorf embarks on a trip to Henrietta Hudson, a lesbian bar then at the heart of New York City queer nightlife. Her recount, reminiscent of a zoologist on safari, details, among others, a “sexy young tawny-skinned woman in her early twenties (...) talking to her pretty blonde lover, also in tight jeans.” She finishes by affirming “these are the faces of a new generation of women - women who have transformed the lesbian image.” Clearly, to Jeanie, and to the writers who followed suit in documenting this new fad, the secret to the success of the grand lesbian rebranding lay in the willingness of these ‘new’ women to integrate into wider society. Gone were the butch women of the past in ill-fitting men’s clothes with cropped hair - these lesbians cared about how they looked to heterosexuals. Better still, they strove to look like them: skinny, feminine, and - as an added bonus - well-dressed.

This first incarnation of ‘lesbian chic’ set the tone for nearly every iteration to come. Lesbians, finally, were cool. Well-groomed and perfectly outfitted, not only were they washed clean of the aesthetic eyesore tendencies of their past, but women and men alike actively wanted to look at them. For straight women, they represented the cosmopolitan ideal: at work, they rocketed towards the glass ceiling, pioneering gender-bending office-chic with the fortune of being untethered to procreational pressures. In their downtime, blessed with the budget for sleek in-season clothes, they and their equally glamorous ‘lovers’ could exist in a glossy universe free of the lesser sex.

Men, conversely, were finally being granted voyeuristic access to a world from which they were once exiled. These new lesbians, having shed the tight-fisted anti-patriarchal skins of their predecessors, finally looked just like the women in magazines. In conceding to the trends, these lesbians had given men a stake. Even better: there were often two of them - and they were strictly off-limits. Though the August 1993 Vanity Fair shoot wasn’t styled for men to gawk at lang, they were given sex symbol Cindy, scandalously draped over her. They could put themselves in lang’s shoes - literally - but the photos almost seem to whisper “I could have you, but I’d rather have her.” Moreover, these new, beautiful lesbians presented men with a challenge: in looking the part, they could almost be perceived as not having sworn off heterosexuality entirely - that was for the real dykes. Maybe, if they wished and pursued ravenously enough, men could claim a part of this untarnished woman for themselves; rescuing her from her flirtation with true radicalisation before it was too late.4

Though it’s considered that the first wave of lesbian chic saw its true heyday between 1993-4, it’s worth noting that the concept remained present in - at least middle-class, cosmopolitan - culture throughout the 90s5. In Sex and the City’s 2nd season, airing in 1999, Charlotte - traditionally the group’s most conservative, in a Ralph-Lauren-catalogue, WASPy-wet-dream kind of way - finds herself briefly inducted into a group of New York City lesbians6. As they browse big-ticket paintings in the SoHo gallery where Charlotte works, Carrie narrates: “Power lesbians and their shoes are like Wall Street brokers and their cigars.” To Charlotte, these women embody her ideal life: after going for dinner at a “hot new restaurant” with an “even hotter sapphic chef”, she joins them at two separate lesbian bars, feeling “exhilarated and happy as she’d ever been”. In Carrie’s words: “There was something relaxing and liberating in travelling through an alternate universe that contained no thought of men.” Not only were these women wealthy and successful, they were beautiful, cultured, and always at the height of fashion - “Manhattan’s chicest new social hive.” At the very least, shockingly, the lesbians shown here were not all white - but the precedent remained, and lesbian chic was here to stay.

The mainstream revival of lesbian chic came with the 2004 premiere of The L Word on Showtime. Advocate magazine announced its return with a cover story about the show: ‘Lesbian Chic: Part Deux.’ Though The L Word represented a shift away from the outside-in treatment of lesbians in mainstream media, it again carried the burdens of the lesbian chic precedent. The lead characters, (mostly) white7, cis-gendered women living in LA, were - once again - wealthy, successful, well-dressed sapphics whose existence posed no threat to incumbent beauty standards or heteronormative hierarchy. To me, it is with The L Word that we see the solidification of the ‘good lesbian/bad lesbian’ dichotomy. The lesbians ‘good’ enough to secure their place on TV are repackaged for heterosexual viewers at home, with their sex lives graphically on display for external consumption. The show, though intended to showcase the lives of a group of lesbians, centres around Jenny Schecter, who starts the show as a straight, small-town girl moving to LA with her boyfriend. Upon having an affair with Marina, a (feminine) sultry woman of few words and vague European origin, Jenny is a convert. Whether intentional, the show places its established queer characters - only half of whom are played by actual queer women - in Jenny’s orbit. As much as the show made strides for any lesbian representation on TV, in sticking to only ‘good’ lesbians - the most transgressive it dares to get is with Shane, an androgynous seductress (a razor-thin, white one at that) - it cements that the only lesbianism deserving of airtime is one rooted firmly in conformity. ‘Bad’ lesbians, that is to say, those who are genderqueer or masculine-presenting, are best swept under the rug, to be neither seen nor heard. Besides, who would want to watch them?

Following The L Word’s finale in 2009, lesbian chic in its purest form has yet to resurface with true strength. Apart from a smattering of articles in the 2010s, it was never in to be sapphic - until today. Christened perhaps by a New York Post article in the summer of 2022 titled “‘Dressing like a lesbian’ is sexy, ‘powerful’ new trend”, touting the cringeworthy opening line “Lesbi-honest, queer fashion is totally in!”, these last few years have opened a window for a revival of lesbian chic - a lesbian renaissance. Hard on the heels of a landmark decade for queer representation, with 19 countries worldwide legalising same-sex marriage, and a proliferation of queer celebrities and media (with RuPaul’s Drag Race peaking in popularity, a Queer Eye revival8, and a slew of out high-profile celebrities) into the mainstream, lesbians could once again fight for their moment in the spotlight, and fight for it to be done right. Perhaps this time, we could follow in the footsteps of gay men and establish a permanent place in popular culture. Maybe the days of fighting against the fate of one-season cancellation, which all TV shows with sapphic leads are cursed with, were behind us. And maybe, just maybe, the world could be ready for all lesbians, not just the good ones.

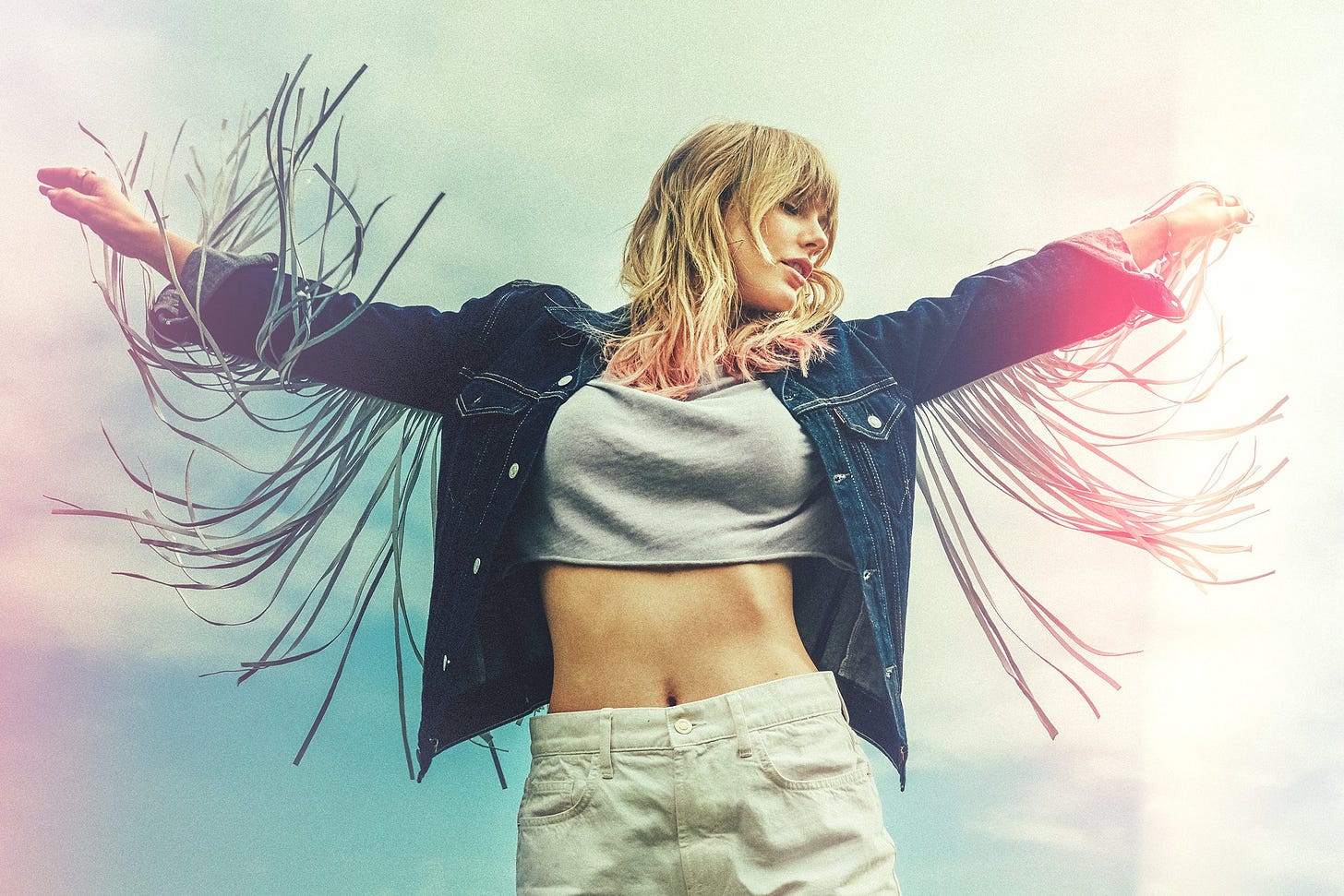

Enter Chappell Roan. At the time of writing, she is Spotify’s 74th most-streamed artist worldwide. She’s even playing over the speakers of this little Buenos Aires café as I type. This Sunday, she’ll perform at the 67th annual Grammy Awards to a live audience, broadcast to screens worldwide. I think I’d face little pushback if I said plainly: she is our best candidate for this renaissance of ‘cool’ lesbianism9. She’s outspoken, politically active - but she’s also intelligent, well-spoken, and incredibly beautiful. Her music has, and rightly so, been received to widespread acclaim: bluntly, she makes great pop. It’s danceable, cheeky, and so much fun. For the masses, she’s brought gay-club-girls’-nights into the home (and indeed, to festival grounds), and for us lesbians, she’s everywhere - and she’s very, very, loud about exactly who she is.

It is here that I encounter my dilemma. As much as I adore Chappell - and it bears repeating that I do - what does it say that she is our best candidate? To reduce this to merit, many other sapphic artists make music of equal quality. As they say in the industry, anyone can write a hit - so why has Chappell struck gold? I look to MUNA, the all-sapphic pop band who opened for Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour for some of its North American leg: they played nightly to an audience far larger than Olivia Rodrigo’s, but saw little to no increase in listeners. I couldn’t help but ask: is the world really ready for us?

Chappell is, ultimately, a conventionally attractive white woman. So negligible is her queerness to many, that despite the overtly sapphic content of most of her songs, I found myself wading through swathes of TikTok comments denying her lesbian identity. Chappell, to my count, has had to publicly come out as a lesbian three separate times. The most significant, to me at least, was her August 2023 Pitchfork interview, wherein she declares (again) that not only is she a lesbian, but that “I don’t think [men] understand me, and I don’t think they make good art.” Arguably, her constant re-insistence of her sexuality could just be due to the rapid rate at which she was reaching new audiences, and why would they assume she’s queer? Dancing to HOT TO GO! in your room isn’t a natural precursor to an ‘is Chappell Roan gay’ Google search - and perhaps this is a good thing.

However, I do have to question the implications of her role as, debatably, the most popular lesbian in mainstream media. Though the visuals of her on-stage persona are infused with references to queer culture - drag, of course, being the main one - to the uneducated eye, she is just a girl in costume. Drag, ultimately, represents the subversion of heteronormative gender presentation by its wearer. Chappell, in paying homage to drag queens and their hyper-femininity, reads to many heterosexuals as simply a pop star in extravagant dresses and stage makeup. Of course, this is not me overwriting her choices to queer her every action - I applaud her for it. But based on her reception by the general public, I worry it falls on deaf ears. More pressingly, I worry it unfurls a dangerously regressive path for the future of mainstream lesbian representation. If we continue to comply with ‘acceptable’ lesbianism - that is to say, conventionally beautiful, feminine, white women - at what point will we have sealed our fate? As much as we should applaud any lesbian that breaks into the mainstream as unapologetically as Chappell has, at what point are we toeing the line of complacency? How many times will we allow ourselves to be boxed into conformity, having our identity reduced to the summer’s hottest trend, endlessly allowing the ‘good/bad lesbian’ dichotomy to reinforce itself - after all, all press is good press - before we deign to ask for more?

I turn again to MUNA, a band whose members are lesbians of colour, and genderqueer - granted, all are still conventionally attractive - and ask why they can’t also enjoy the same level of success. Or up-and-coming artists such as Cat Burns, or Nxdia10: why haven’t they broken beyond ‘gay fame’? Granted, Chappell stands apart as the first true ‘pop star’ to be vocally lesbian - she stands alone in her rank alongside the likes of Sabrina Carpenter or Beyoncé. Though Billie Eilish has recently spoken openly about her queer identity, Chappell is the first in this realm to fiercely defend her identity as a lesbian - a word dripping with so much negativity that even many of us who identify as such have shied away from using it in recent years. Of note also is the willingness of fans to throw it back at her when she is perceived as stepping out of line. Her recent clashes with fans and paparazzi - and rightfully so - over boundaries and her treatment as a celebrity saw a dizzying online response, much of which was laden with lesbophobic insults, from straight women and gay men alike. But this shouldn’t have to stop us from asking whether this is all that we’re willing to take. Though we shouldn’t have to, shouldn’t we want to fight for representation? Shouldn’t we, lesbians in all our forms, want to see ourselves, our actual selves, among the artists in the charts, and the characters on TV? Isn’t this what representation is all about? If we allow ourselves to be sanitised, time and time again, by all that is ‘palatable’ for mainstream audiences: when will their tastes change? Chappell, for all her merits, is yet another example of the trappings of the ‘lesbian chic’ phenomenon: a woman whose sexuality the public is willing to overlook, or even tokenise, due to her willingness, or ability, to conform.

All this to say, I am beyond proud of all that Chappell has achieved, and the promise her career holds. I write this only to encourage us, as lesbians and allies alike, to strive for more. We deserve representation for all lesbians - and we shouldn’t allow the mainstream to dictate what facets of our identity deserve airtime. I hope that going forward, we continue to champion equally talented sapphic artists, regardless of how they appear, all the way to the Grammys. I dream of a future where Chappell is not the only lesbian artist with multiple spots in the Global Top 100. I dream, perhaps idealistically, of a masculine-presenting sapphic pop star; a trans lesbian pop star11; or a lesbian pop star of colour. We deserve a lesbian renaissance, make no mistake, but we deserve one free from the compromises of lesbian renaissances past. We deserve better.

I’ll speak on my gripes about the girls-fooling-around, ‘phase’-adjacent trope at some other point, rest assured

Like much of this essay (though swung far in the opposite direction), this is sarcasm.

Don’t get me wrong - I love this. See also: Joan Armatrading, Janis Ian, The Japanese House, Adrianne Lenker

Just in case it bears repeating: more sarcasm.

What I will not touch on is the 2000 straight-to-TV movie ‘If These Walls Could Talk 2’, where Ellen DeGeneres and her wife discuss, among other things, the possibility of having an ‘ethnic baby’ (cue groaning)

This episode contains one of my favourite Samantha quotes ever, if you’re interested: “You can’t expect to move to Wonder Woman’s island and not go native!”

I’m aware that Bette is biracial, but she’s close to being white-passing, and her sister Kit is relegated to side-character status.

And an L Word revival - one whose cancellation I unironically mourn (go watch it!)

Note: of our available options at her status

See also: Shygirl, Rachel Chinouriri, Maude Latour - I would mention Rina Sawayama, but we’re talking about merit, so….

But please, not Kim Petras. Not until Dr Luke is out of the picture.